While memorising lists of words and grammar rules is one of the most common ways to learn a language, it is also one reason many people end up quitting. It usually takes many hours of senseless repetition – there’s no fun in that and the results are mediocre at best.

In this article we are going to talk about a different approach towards learning a language. It uses your natural abilities and enables you to have your first basic conversation within 3 months.

We are going to tell you the science behind it and how we implemented it in our application, Taalhammer.

- The real need for a new language learning app

- What is your real challenge?

- How did you learn your native language?

- Learning grammar is against our nature

- Grammatical rules should not be ignored, though!

- Why can’t adults learn a language like children?

- Why are adults better at learning languages than children?

- 5 reasons why you should memorise sentences for language learning

- Why learning 1000 words won’t lead to understanding

- The fastest way to the first conversation in the foreign language

- Start with the fundamentals

- Learn the content applicable to your own life

- Memorising sentences is not enough

- More literature

The real need for a new language learning app

But let’s start at the beginning.

We are two Polish guys. We met in Amsterdam, where we worked as software engineers. We both wanted to learn Dutch, and we wanted results fast. It turned out we had more in common than we thought. We have had significant experience studying foreign languages since 1990. Since then, we have used every possible language learning app and have participated in classroom courses over the whole world.

We were more successful in some languages and less successful in others.

We shared the same negative experiences, especially when it comes to wasting many hours on learning grammar and not being able to use it in conversations.

So we started reading about memory hacking techniques and language acquisition. We focused on experimenting with combinations of existing techniques and how to support this with smart software engineering.

We did not care about mistakes and perfection, we wanted a quick way to be able to start talking to Dutch people. Something that would develop a reflex, so we would be able to automate certain things in the language.

One method stood out. It delivered what we wanted and led to extraordinary results!

What is your real challenge?

The human language is a very complex system. This makes it very difficult to learn any foreign language.

The problem starts with the fact that every language has tens of thousands, or even hundreds of thousands of words. English has supposedly 170 thousands words (although educated native speakers use only 15 to 30 thousand of them). Words describe activities, actions, things, people and their attributes. Without words you cannot express your ideas or understand the ideas of others.

You will need ca. 3000 words to have a meaningful conversation on a non-trivial topic. And it is very difficult to remember the meaning of 3000 words.

Things get worse. Remembering meaning is only half of the problem — you also need to remember how to pronounce them. And unfortunately, in most languages, the pronunciation is not always the sum of the letters in contains, e.g.:

- in the word ‘extremely”, each of the e’s is pronounced differently.

- the letter combination “ough” is pronounced differently in “hiccough”, “thorough” and “through”

So you need to memorise the pronunciation of the words as well.

The complexity does not end here. In a language, words very rarely occur in isolation. What happens is that words combine with other words to form phrases, and not every combination of words is valid. So you just need to learn that “to do homework” is correct while “to make homework” is not.

In order to have a conversation, you need to go a step further and combine words and phrases into sentences. And again, only very specific combinations are considered valid. You just have to know that “I am cleaning the house” is correct, while “The house am cleaning I” is not, although both variants are understandable. If you can’t build sentences you will not be able to speak.

Now consider that in order to speak fluently you need to produce words at a rate of ca. 120 items a minute, in the correct order and combination and pronounced in the right way.

Learning a foreign language is indisputably a very complex task which takes a lot of time and effort.

There is no workaround that would magically help you to learn a language in a month or two. Everybody who tells you this is possible is a liar.

How did you learn your native language?

Language has a lot of properties that can best be understood as being statistical. Frequency of occurrence plays a key role.

It becomes obvious when you think, for example, about language change. All human languages change through time, just by being used. Just watch English movies from the 60s and you will see how different the language was then compared to today, only 60 years later. They change a lot, in all aspects, like sounds, structures and words.. With every change, the old way is being replaced by a new way. So what determines this new way?

The answer here is: the new way is the most frequent way of understanding a sentence or expressing a thought.

Think about the words “quick” and “fast”. They seem to be synonyms of each other when used in isolation. So why is it that collocations like “a fast car” or “fast food” are correct but not “a quick car” or “quick food”? Or why “a quick meal” and “quick shower” but not “a fast meal” and “fast shower”?

The answer here is: because particular words frequently group together. It just so happens that “fast car” is being used more frequently than “quick car”. There is no other reason.

Natural language is a probabilistic system. This means that probabilities, and not rules, decide what is considered correct and what not. Everything in a language works according to probabilities: word order, tenses, sounds, pronunciation etc.

Now, our brains and the language co-evolved and they adapted to each other. In other words, our brains are extremely good at recognizing patterns, frequencies and regularities and extracting the underlying structure!

Moreover, to facilitate fluency, our brain does not usually store individual words. Rather it stores combinations of words (or even whole sentences) as one piece in the memory. These pieces are called “formulaic sequences”. The simplest example is “I don’t know” – every time you say it, you retrieve it from your memory as a whole.

This is exactly how you learned your native language when you were a child. You were just listening to your parents saying different things and nobody told you any rules. With time you have just figured out what is correct and what not.

You have developed a “native instinct”. Without any knowledge of grammatical rules.

Learning grammar is against our nature

After reading all relevant research, one thing became clear to us.

Grammatical rules, as well as their exceptions, are just a way to describe human language – but they are not the system itself!

This is where, in our opinion, a lot of language learning methods are making the biggest mistake. They teach you grammar rules first. They assume that you can learn a lot of words and grammatical rules and then, when speaking, do a kind of mathematics, i.e. generate sentences by combining the words by applying the rules.

Our brains are very very inefficient at doing this.

Trying to understand and master a language by first learning grammatical rules is against our own nature.

We are not saying that it is impossible to learn a language like that — it just makes it unnaturally difficult. It is like learning to ride a bicycle by reading about balance and torque! Or learning music with only musical notes and covering your ears so you do not hear the sounds. Yes, it is possible, as Beethoven has proven, but it takes a genius to do it well.

Grammatical rules should not be ignored, though!

In our experiments, we found out that rules work well as references.

This means that you should first discover the structure of the language (e.g. through memorising a representative amount of sentences, as described later in this article) and only then look up the grammatical rules. That way it is much easier to remember it and to use it while speaking.

Imagine you are learning English. Look at the following sentences:

- I know a tall man.

- They know a lot of girls.

- He knows that girl.

- She talks a lot.

- She likes tall men.

- We talk a lot.

As soon as you memorise them you are going to recognize some patterns. Very likely you are going to see that the verbs (knows, talks, likes) always end with an “-s” if the subject is ‘she’ or ‘he’.

Now we will tell you the rule: always add an ending “-s” to a verb in the third person singular. Two things will happen:

- You will find a confirmation of the discovered hypothesis

- You will classify the previously learned sentences as a group (as your brains love classifying and grouping).

This will allow you to automate how you speak, so more often than not what you will say will be correct. Even if you will not be conscious of the actual rule.

Learning in this order enhances your language acquisition in a natural way.

Why can’t adults learn a language like children?

A common misconception is the idea that you can learn a language “like a child”.

Adults cannot learn “like children” because we cannot repeat the same experience that children underwent.

Why is that?

- When children learn their first language, their brains and their speech apparatus are still under heavy development. Their brain just works differently! It makes children absorb the whole of the language like a sponge. They can memorise huge amounts of words and sentences without knowing what they mean or how to use them. They can also masterfully imitate whatever they hear. Hardly ever will adults be able to recognise and produce sounds with such precision.

- The language children learn is integrated with areas of the brain responsible for sensorimotor skills like seeing, hearing or touching. This means that access to the language will be faster and speaking it will require much less effort (as easy as moving your hands, for example). This is why we feel so natural when we speak our first language. Hardly ever, and only with great effort, are adults able to learn a language so that it comes so naturally and effortlessly.

- Children are not intentionally trying to remember the language they hear. They don’t analyse – they just experience it. In other words, children don’t use their declarative memory – simply because it has not developed yet. Most adults analyse everything, judging themselves and consciously putting effort into understanding. Ultimately this is why adults have so many difficulties. You can read details about this phenomenon here.

- Children learn all the time! Their whole life is about interacting with their environment and trying to communicate. Adults, on the other hand, can dedicate a limited amount of time to language learning as they usually have many other responsibilities.

You can’t turn back time to become a child again.

But that does not necessarily mean that children are better at learning languages!

Why are adults better at learning languages than children?

Think about language learning from a different angle now. It takes children ca. 5 years to speak a language! And even then their language is quite primitive and there is not a lot they can talk about.

I bet you can do better than that.

You have quite a few advantages compared to children. Some of them are:

- You have already learned one language (i.e. your native one) so you are aware that there are multiple languages and you have the ability to translate from one language to another.

- You understand how the world works and you have more information about it. That makes you able to talk about many different topics and see similarities and differences in what you learn.

- You are aware that you are learning and you can do it in a methodical way, so you can choose what works best for you. (This, of course, is only an advantage if the methodology you are using is actually enhancing your learning!)

And more importantly, despite all the differences between children and adults, the method of learning a language remains the same: repetition and trial-and-error.

Having realised all this, we saw a great opportunity to design a language learning method that really works.

What if we used the same principles that worked for children but adapted them to the advantages we have as adults?

And what about if we curated the content we learn in such a way that it will ideally fit into the way our brain processes information?

But what is the best content to learn the language?

Well, it is exactly what we use when we speak a language.

Sentences.

5 reasons why you should memorise sentences for language learning

Some time ago we stumbled upon the idea of learning a foreign language by memorising sentences. You can find it yourself by googling for approaches like “10000 sentences method” or “sentence mining”.

Although intuitively we felt it is the right thing to do, it took us years of research and practice to fully understand why.

It is a natural way of learning

Unless you are a scientist, your goal in learning a foreign language is to be able to engage in conversations. And in order to do this, you need to speak using sentences.

Memorising sentences is a natural way of learning a language as it allows the brain to do what it does best – processing patterns and extracting the structure out of it.

If you memorise whole sentences, your brain will recognise the patterns and you will unconsciously learn the structure of the language. You will start “feeling” the grammar, i.e. you will recognise what is correct. More often than not you will produce correct sentences without knowing the rule behind them.

Very quickly you will be able to produce new, original content, i.e. sentences that you have never heard or seen before.

But that’s not the only reason to learn this way.

In increases your confidence and motivation

Especially at the beginning of the learning process, every conversation is very stressful for you. And the more stressful it is, the more difficult it is to find words and rules and combine them into sentences. This is why we often freeze or mumble something.

If you memorise full sentences, you don’t need to do any “mathematics”, you just say the sentence as a whole from your memory. This also increases your confidence and motivates you to learn further.

It teaches you how words work in context

Sentences show you how words function in context. This is not only more memorable, but also helps you to learn how words are actually used. Seeing the same word or grammatical item in different contexts will help you absorb how it should be used in other sentences, as well.

It teaches pronunciation

You expose yourself to how the language sounds. This is crucial at the beginning, when you learn to segment speech into words i.e. recognise where a word ends and where the next starts. It also improves your pronunciation and intonation. You will sound more like a native speaker.

It is more fun

It is more fun than just memorising words and their translations, so it will keep you engaged for longer. You will progress more quickly and so be more motivated to continue learning.

Why learning 1000 words won’t lead to understanding

Have you ever heard of Zipf’s Law?

It describes the frequency of words in languages. In essence, it states that a relatively small number of words make up the majority of the spoken language.

We put this law to a test. In English, for example, it takes 9 words to cover 25% of spoken and written language. The words are: and, be, have, it, of, the, to, will, you.

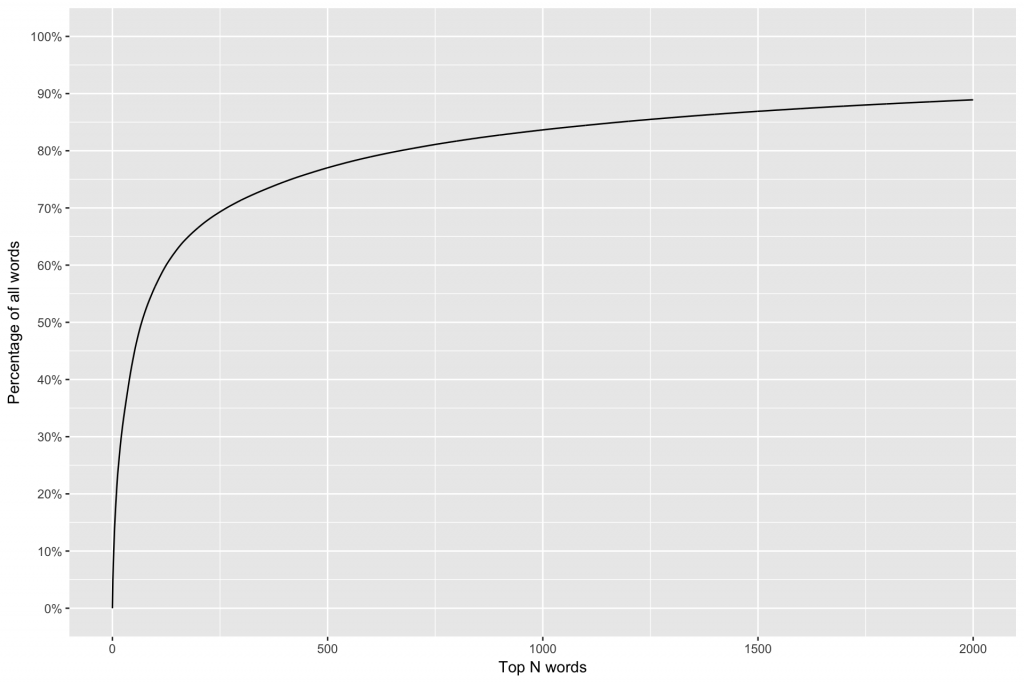

Here we have plotted cumulative frequency for the top N words in English:

You can see that you would only have to learn the 500 most frequent words to understand ~77% of all words, 1,000 for ~84%, and 2,000 gets you to almost 90%.

The 1000 most frequent words are called the core of the language. This is the base of the theory that it is enough to learn 1000 words to speak a language.

But here’s the sad truth.

If you learn a list of the 1000 most frequent words, your understanding of a language will be close to 0%. Why? This is because these words are only filler material in the language. The other 20% convey the real meaning!

We call these 20% the peripheral vocabulary.

Think about it this way. Every person has different needs for a language depending on their interests. A musician’s language is different from an engineer’s, which is different from a businessman’s. What they have in common is the same core; where they differ is the periphery.

Don’t get us wrong. It is absolutely essential that you learn the core of the language. What we say is that doing that alone does not lead to language comprehension.

A good analogy to understand why is to think about the construction of a building. First, you would clear the foundation, and then you would build a skeleton structure made of steel beams. At this stage, it would not look like a building you are familiar with since there are no walls, windows or decorations. However, a solid structure is first necessary before you can have anything resembling a building.

The same is true for language. First, you must have a solid foundation that is composed of core words. Once you have that then you can easily add the more aesthetic elements.

Most courses and apps try to give you something that appears like a completed building already, but without the proper foundation.

At Taalhammer, we recognise the importance of both.

On one hand we offer Core Collections, where you can build very solid fundamentals, regardless of your current level. There are always structures that are problematic to learners and need to be masters and automated. On the other hand, we offer a tool to extend your peripheral vocabulary. More details below.

The fastest way to the first conversation in the foreign language

As soon as we understood the relationship between the core and the periphery, we realised what it takes to have a first conversation in a foreign language: a solid foundation and some words and sentences around the topic you want to talk about. In the next few paragraphs we will explain both of these aspects.

Start with the fundamentals

So how did we build the foundation?

We have applied advanced statistical methods to compute the most frequent spoken words. Out of those we selected verbs, nouns and adjectives, as these words convey the most of the meaning in the language. Finally, we wanted words like “go” and “going” to be considered one word, so we extracted the base forms (i.e. lemmas) out of all selected words.

Initially we were concerned about our verb-centric approach, as verbs are complicated because of the conjugation. Moreover, frequently used verbs are often irregular verbs, thereby increasing complication.

So then we started to generate sentences using those words. We were looking for sentences that will be easily remembered and processed by our brains.

We experimented a lot and learned several thousands of sentences by heart. After several months it turned out that the verb-centric approach is not a problem. Given enough variations our brains pick up the complex conjugation just fine.

We also came up with the following principles for perfect sentences.

- They must be short, optimally between 3 and 7 words.

- Each sentence must represent a particular grammatical or communicative pattern.

- At least 60% of each sentence should consist of words you know.

- Sentences should use the core of the language (the 1000 most frequent words).

- Sentences should be ordered in increasing complexity.

Using those principles we have carefully created ca. 4000 sentences. These sentences are the base of our Core Collection, which we offer at four difficulty levels: absolute beginner, beginner, pre-intermediate and intermediate. Each of those collections will provide you with the foundation you need to construct grammatical sentences without the knowledge of grammatical structures.

Memorising our core collections will develop native-like reflexes and train you in building sentences.

But it is still not enough to have a conversation.

Learn the content applicable to your own life

Have you ever heard of Stephen Krashen and his hypothesis of “comprehensible input?”

According to Krashen, we acquire language in only one way: when we understand what is being said to us.

This idea was very compelling for us and we tested it a lot in our initial experiments with Taalhammer. We memorised a lot of sentences in different languages and we talked to native speakers online. At the end we tested ourselves on how much we remembered.

With time it became clear that real magic happens when you engage in natural conversations, in which you are focused not on the form of what you say, but the communication itself.

And the best way to do that is to talk about topics that:

- you are interested in

- you have something to say about in your native language.

That way the sentences mean something more than just the words that they consist of.

Here again, most of the current language learning methods and apps make a huge mistake. They teach you situational language that is not applicable to your own life, something that you would not usually say outside of the context of the course. You would learn words, such as giraffe, moon, and crepe, but if you don’t specifically want to make a reference to giraffes, moons or crepes, then they would not be too helpful.

As soon as we realised this, we also understood that language learning must be personalised. We experimented with several AI algorithms and we even tried to use what Facebook knows about us.

But then it finally dawned on us.

You need to take control over your language learning and create part of your curriculum. There are two reasons for this:

- You best know yourself and what is applicable to your own life;

- You remember much better if you choose the content you learn yourself.

This is why we created the Hammer Editor, a place where you can personalise your learning without special effort, as part of your natural interaction with the app – when checking the meaning of words, or searching for example sentences around the topic of your choice. We also built in auto-translation for your own private examples. All in one place.

With one click, Taalhammer will make sure you will remember your examples forever.

Memorising sentences is not enough

Of course, we are not claiming that you should just rely on learning sentences in isolation. In order to truly learn a foreign language, you need to do other things as well: repeat a lot, speak it and listen to it.

Repetition

Over 100 years of research shows that information is lost over time if you don’t try to retain it. In practice this means that, if you do not repeat systematically, you will forget 90% of what you have learned within the first month. The phenomenon is referred to as the “Forgetting Curve”.

The best way to retain information is to repeat your sentences with some variant of a spaced repetition algorithm. We have described our implementation of this in this article on “How to hack your long-term memory for language learning”.

Speak the language

You need to practise speaking the language. A lot. Optimally you should regularly have lessons with a tutor, online or offline. You can read this article about how Taalhammer can support the relationship between you and your teacher.

If you live in a country where the language is spoken, your possibilities are endless. If you need inspiration on how to prepare yourself for the first conversation with a native speaker, read this article.

As described earlier, during conversations there is no time to build sentences out of words by applying grammatical structures – especially in the early stages, when each conversation is very stressful. Learning with sentences is one of the best ways to prepare for these conversations.

Listen to the language

There are two types of listening: active and passive.

In active listening the goal is to repeat and understand the content that you have learned. If you combine this activity with learning sentences, you will discover even more structure in a language.

Taalhammer offers a hands-free Listening Mode where you can listen only to the sentences that you have learned before. This trains your ear and helps memorising even more.

Use while commuting, jogging, in the gym etc.

The goal of passive listening is to enjoy and not to understand. Listen to a radio station or an audiobook in your target language – you will train your ears and get used to the real sounds of the language.

It has been a long journey for us and in the process we managed to learn a few new languages on the way. But the journey has not finished yet! At the end of the day, we are language geeks. We experiment with new ways and ideas of learning every day and implement the ones that work into the Taalhammer app.

If you are learning Dutch, German or Italian look at our courses descriptions.

Start learning a foreign language with Taalhammer. Go to www.taalhammer.com and sign up today.

More literature

- Stephen Krashen, “Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition”. (link)

- Nick Ellis, Rita Simpson, “Formulaic Language in Native and Second Language Speakers”. (link)

- Ricardo E. Schütz, “Stephen Krashen’s Theory of Second Language Acquisition”. (link)

- Patrick Rebuschat and John N. Williams, “Statistical Learning and Language Acquisition”. (link)

- Jürgen Meisel, “First and Second Language Acquisition”. (link)

- Barbara C. Lust, “First Language Acquisition: The Essential Readings”. (link)

- Jenny R. Saffran, “Statistical Language Learning: Mechanisms and Constraints”. (link)

- Steven T. Piantadosi, “Zipf’s word frequency law in natural language: A critical review and future directions”. (link)

- “Why are adults so bad at learning new languages? We may be trying too hard”. (link)